Science fiction is the most shocking, the most horrific, the most terrifying literature of the modern age. It’s been that way for more than 200 years. So why is it consistently undersold?

It’s not the same with movies. With science fiction horror movies you know what you’re getting: it’s there in the poster. A hideous egg cracks open. Rays of icy light shoot from the hood of a stumbling figure. Hallucinogenic visions slice the darkness of a ringed planet. But books — no, books seem too timid to use the iconography of horror that is rightly theirs in case they somehow alienate potential readers.

To illustrate what I mean, let’s explore two very similar works: E. C. Tubb’s 1983 novel Stardeath and the 1997 movie Event Horizon.

For sure, Stardeath has the shlockier title. It probably wouldn’t work as a movie title, unless it was low budget and exploitative. But my belief is that Tubb needed a title this direct in order to alert readers that it wasn’t just another space opera or some kind of genteel spacesuit drama. By and large, books have to sell themselves on the thing in your hand. Movies get trailers in which tone and mood can be examined.

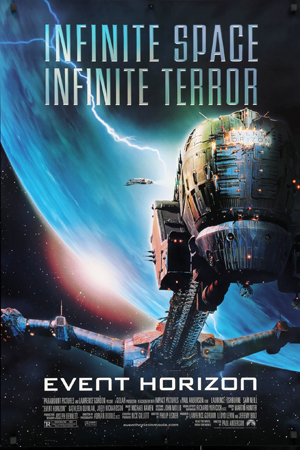

Here’s the poster for Event Horizon:

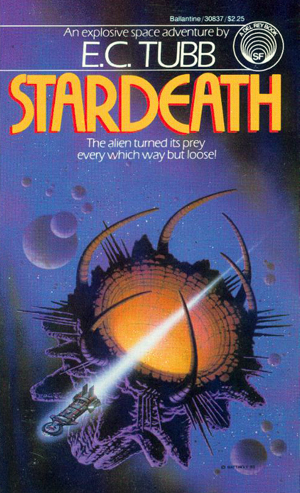

And here’s the first edition of Stardeath, illustrated by David B. Mattingly:

They’re superficially similar. But one of them feels like post-Alien horror, grim and haunted. It uses trigger words like “terror” to make its theme clear. The other seems to want us to believe that it’s some sort of golden age science fiction.

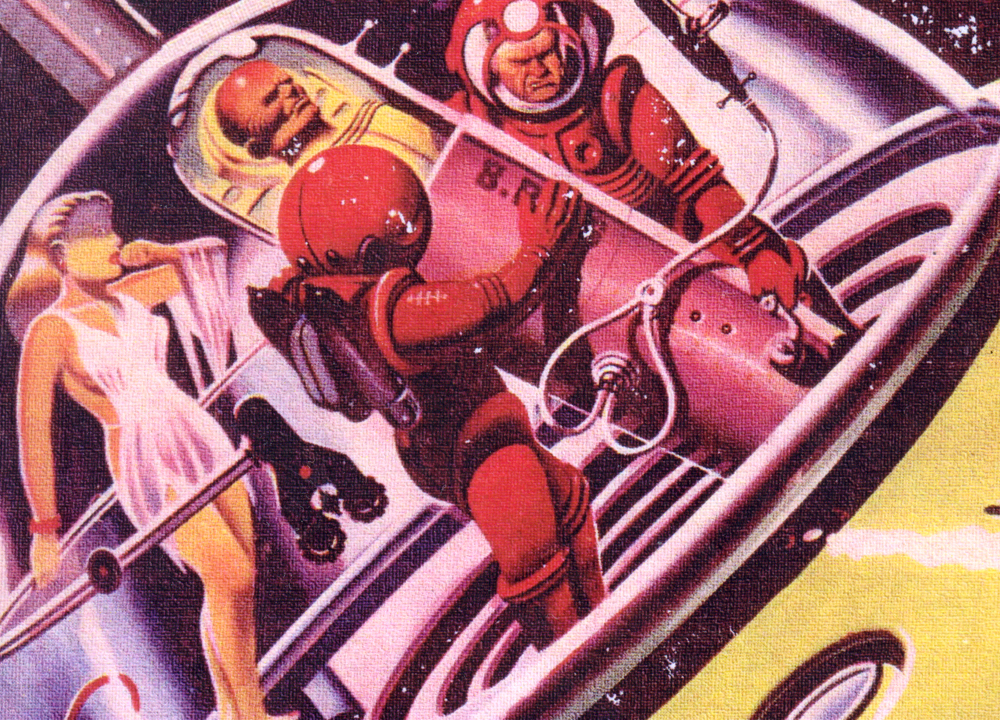

It’s worse in the book’s second edition from 2005, which is the one I own. This edition was published by the somewhat tawdry Wildside Press, had clearly and ineptly been run through OCR (the hero’s name alternates between Jarl and Jan!), and slapped on a pulp magazine illustration to make its oldy-timey sci-fi sale more obvious still:

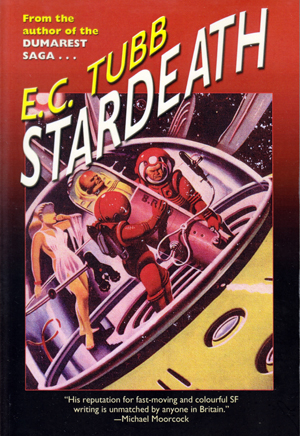

Wildside has reprinted it since, and this time with a cover that looks a little darker, a little more unpleasant, but still has nothing of the visceral dread of the Event Horizon gothic castle in space:

The plot of Stardeath is simple and cruel. Travel through hyperspace (what the novel calls “hydee” for hyper-drive) has been invented, but there’s a problem. A small proportion of ships that use the drive disappear without trace — I’m guessing it’s about equivalent to the number of our own airplanes that crash. In other words, an acceptable loss, except of course that the most high-profile losses are the ones with the most passengers.

Then there’s a break. One of the missing ships, the Lewanna, has been found adrift in deep space. Most of her 300 passengers and crew are dead, mercifully. They’ve been slaughtered in gruesomely inventive ways, some of them turned literally inside out. But a few of these mutilated unfortunates are still alive, still somehow dragging their monstrous, lacerated bodies through the blood-slicked corridors of the ship.

We follow an investigative mission on the ship Odile which tries purposefully to attract whatever force it is that has been attacking the ships. It succeeds. The Odile is cast beyond hyperspace into a hellish region and brought face to face with an outrageous alien monstrosity against which it has no direct defense. The crew are plucked helplessly from their posts and churned into living pastrami.

Eventually the Odile manages to find a way back to our space, but there’s no beating this adversary. All mankind can do is hope to use the hydee without attracting its attention.

All these beats are repeated in the much later movie Event Horizon, except that it grafts on literal hell just for the heck of it, has a character that morphs into some sort of devil, and cloaks everything in an over-the-top haunted house design just so you get at a glance that this is intended as a creepshow.

Sure, the plot is derivative, but director Paul W.S. Anderson likely hadn’t heard of Stardeath. He based it on the 1987 game Warhammer 40,000, which itself feels highly derivative of Stardeath but was likely extrapolated mostly from Michael Moorcock novels with some Chthulhu mythos grafted on.

I really like Event Horizon. It’s chortling good fun and it’s nicely horrible. But Stardeath is bleaker and more horrible and a much more satisfying nightmare. So why is the movie plainly a form of horror, whereas the other is burdened with its straight science fiction tag?

There are three types of horror story, as far as I can see.

Let’s call the first type the horror of the known. It involves the world we see around us, including the people with whom we must share our lives. It encompasses the serial killer in the suburbs, the rogue shark in the water, the crashed plane in the desert, the kids who venture out of their depth.

To me, known horror is the laziest type because its fears are generally mundane. It’s hard to care about the literature of abusive men when we are all so used to abuse since we all live with it. The stronger adversary is simply another bully, and the fact that we understand them makes them less horrific and more something we need to endure like a bout of illness. Even psychological horror is merely a means of coping with what we all cope with on a daily basis, the stresses inflicted on ourselves by the world we’ve built and seem incapable of reforming.

I’ve written stories and novels of this type (The Music Of The Rending Of The Night, The Billows), but gimmicks are obligatory and it would never work in the Robert Maas universe.

Above: My novel The Music Of The Rending Of The Night defiantly bucks the trend for the iconography of horror of the known, right down to its purposefully cropped-off lettering (which Amazon won’t allow!).

The second type involves the horror of god. I have a great deal more sympathy for this type simply because there’s a greater scope for religious horror than for the horror of the known. It includes all the spiritual bogeymen, the creatures that won’t die, and the ghosts and malevolent spirits that haunt dark places. Today it is the dominant form of horror fiction.

I’ve written in the style (my novels of the type are Hiding Place, Down Where The Dead Roll, The Summoning, and Poems Found In The Ruins Of A Pagan Commune) but it’s not my focus because the genre generally lacks discipline. Ghosts and spirits can do anything. The undead can rise again — witness zombies and vampires. In fantasy horror, the rules can be hazy, invented to suit the plot even without a scientist’s verisimilitude. It’s also one of the simplest of all things to write, since all you need is a bump in the night or something scratching under the bed.

Above: My god horror iconography is basic because the genre is easily defined. Here’s the shadowy figure of Down Where The Dead Roll and the ghost of the old places in Poems Found In The Ruins Of A Pagan Commune.

The final type is the horror of the possible. In this genre slot all the science fiction horror novels that are not concerned with the world around us but introduce something from outside of nature and technology as we know it: visitors from elsewhere, our own technology used against us.

For me, this is the most compelling and dreadful form of horror since it is never mundane and yet it is real, it is in our universe, and it could happen tomorrow. Arguably, it’s one of the oldest, being the stuff of Frankenstein, and is certainly the most potent. It includes many of the giants of science fiction, including The War Of The Worlds, Brave New World, and Nineteen Eighty-Four. In its own, much lesser way, Stardeath is the perfect encapsulation of the theme: a new technology casts us into the realm of something monstrous.

Much of what I’ve written, and not just under my own Robert Maas name, falls into this genre: Receiver, The Mael, Constant, Residuum, Biome, A Thousand Years Of Nanking, Tessellation Row, Cheer Up Sleepy Gene, Slow Wilhelm Exit, Poems Found In The Wreckage Of A Multi-Generational Spaceship, Grand Funk Central, much of Hemisphere, Shortfall, Good Night Lewton Bus Stop, Harlequin Midnight, The Swallows Of The Dark, and most of my short stories. And yet I call myself a science fiction writer.

In fact, it’s the least of two misconceptions. I would rather be misrepresented for the tropes of science fiction than be thought of as just another peddler of god horror. That’s why even my most horrific book usually has science fiction signifiers on the cover. I can’t help it. I need to limit myself to one understandable genre in order not to be muddled into another.

Moreover, I use the term “smart core” to ensure that none of this work could possibly be mistaken for fantasy and the supernatural. My iconography, therefore, is just as misleading as the rest of the genre, and I presume for the same reason.

Above: Residuum uses an image that suggests a urinal in space…

…in short story collection Born From Ash I evoke the chest-burster of Alien…

…Harlequin Midnight attempts a foggy, hellish feel, evoking a planet of the damned…

…and The Swallows Of The Dark links its otherworldly nightmare to the dark psychological ecstasy of The Music Of The Rending Of The Night.

For good or ill, science fiction literature gives the reader a certain set of associations, a way of viewing the book before you’ve even decided if you’ll read it. I am certain that many more people would read books like Stardeath if they understood that they’re horror laced through with a technological rationale. Such books won’t reach everybody this way — and they certainly won’t attract fans of god horror. But they’ll surely be less ghettoized since horror is now mainstream literature and science fiction largely is not.

Cinema has much more leeway. From Videodrome to Under The Skin and Nope, it trades unabashedly in the horror of the unknown, and receives all the plaudits so rarely afforded to non-horror science fiction. Even TV understands the power of the genre. The series Westworld is just one of a strand of pitiless horror that opens disturbing windows into our future.

But books — still not books. They’ve become the idiot fringe of the culture, and readers need to be spoonfed them carefully so they’re not burned on a form of entertainment it has become a chore to assimilate. What a depressing inversion this is.