I love the man. But I wonder what Harlan Ellison’s legacy is going to be. With The Last Dangerous Visions scheduled for release in 2024, what hope a rehabilitation?

Hang on, Maas, you’re spitting. What the hell kind of rehabilitation does Harlan Ellison need? He’s won more awards than blah blah blah. He’s the most fêted science fiction author since blah blah blah. Nobody’s done more to advance the art and craft of blah blah blah.

Blah blah bloody blah. Sometimes it’s hard to disentangle Ellison the myth from Ellison the maker. And nobody in all science fiction worked harder to elevate themselves above their abilities, or was so bullish about claims of greatness they did not deserve. And I say again: I love the man.

What’s so great about Harlan Ellison? For most genre readers, it’s hard to summon up all but a few thin shreds of enthusiasm. A handful of interesting stories, a Star Trek episode that was never filmed right, a mostly forgotten movie. You couldn’t name a novel by him. Quick, name five great novels by Arthur C. Clarke. No, I only wanted five.

I’m not as huge a fan of Clarke as I am of Ellison, but still. Let’s catapult them both into an arena and have at each other with sticks. Whoops, there goes the music. There are those Clarkean novels, of course, some of the finest ever written under the science fiction moniker. You could also name a host of superb stories — with great plots and everything. You could mention a groundbreaking movie or two. You could talk about geostationary satellites. You could talk, plausibly, about how Clarke acted as an ambassador for the genre, how he became a media celebrity whose opinions mattered, how he enriched and widened the scope of what it meant to be interested in this grubby genre when it most needed it, and how he deepened its verisimilitude and sense of wonder equally at times when both were sorely in need of revitalization.

Clarke towers. Ellison does not. Clarke would have beaten the crap out of him in any rational big-dick competition.

I could equally have thrown Isaac Asimov into the pit, or Robert Heinlein, or H.G. Wells. I could have dropped a layer to important writers such as Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, Larry Niven, William Gibson, John Wyndham, J.G. Ballard, Richard Matheson, Brian Aldiss, Iain M. Banks, Olaf Stapledon, Frank Herbert, Robert Silverberg, Greg Bear, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Tiptree, James Blish, John Brunner, Hal Clement, Stephen Baxter, Kurt Vonnegut, Michael Moorcock, and many more. They’d all have pulverized him.

Indeed, you’d have to go a long way down the genre pecking order before Ellison stood a chance.

And Ellison himself chafed against the idea that he was a “science fiction” writer. Speculative at best, fantasy more comfortable. So where do we start in our bouts between Ellison and the fantasy hall of fame? Even Angela Carter would stomp him to the dust.

What is it about him, then, that provokes such extreme reactions that some will throw up their fists to defend his brilliance while others think him an insufferable hack with delusions of grandeur? And moreover, who will remember a man who died in 2018 at the unresolved height of this polarization — no accommodation in sight then, meaning ever — and is likely to fade further and further as time reduces his memory to an also-ran?

Not many, I suspect. It’s hurtful, I know, but let’s be honest. Most knowledgeable science fiction readers have read only a handful of his stories, the ones that are constantly regurgitated in anthologies: ‘Repent, Harlequin! Said The Ticktockman,’ ‘I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream,’ ‘A Boy And His Dog,’ and maybe a couple others. There’s no representative best of you’d want to pluck off the shelves, and he never made it onto the SF Masterworks shelf (where, I’d say, he belongs) with an anthology of his own work.

One or two of his best stories really are science fiction. The rest are not, any more than you could call Richard Matheson a science fiction writer. Mostly, Ellison’s work is macabre fantasy masquerading as science under the shallowest of rationales.

‘I Have No Mouth…,’ for example, is the story of a magical computer that incomprehensively keeps alive five human beings for eternal torture. After countless decades of mistreatment, they discover the way to release themselves is simply to beat each other to death, duh.

‘Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes’ is nothing more than a Twilight Zone style tale about a haunted slot machine — Matheson would have handled it with far more panache.

Others are the usual fantastic gloop about cosmic powers and super-humans and telepathy and all that lazy quasi-genre baggage that — and here’s the big ta-dah! — editors of the cheaper end of the magazine industry were desperate to publish.

Ellison was proud that he got so many stories into tawdry men’s magazine Knight because its editor didn’t tamper too much with his writing. Well, that editor just wanted the space filled, Harlan. He didn’t care what rot provided the word count. Ellison never got a science fiction story into Playboy (though he did appear there, once, in 1979).

With no genre novels to remember him by, and much too much of a snoot to have allowed third person anthologies of his best work, his reputation now rests on a slim body of stories that hardly anybody reads today and likely nobody will read at all tomorrow. One or two might continue to make it into the bigger science fiction anthologies, but even these will surely fade away given that the genre gets richer every year, the space in overviews is finite, and books in general, let alone anthologies, are on the way out.

In effect, the arresting titles are more memorable than the tales they introduce. Ellison’s foot in the door is through having some of the craziest headlines in a genre known for its crazy headlines. (Though by the way, it appears that ‘I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream’ is not his own invention. It’s the title of the painting that inspired the tale.)

What, then, got him all the genre notice? Ellison played a great game. He wrote like the devil. He learned his craft quickly, and found ways to bash out reams of stories with an angry panache that could be intoxicating. It could also be pretentious and clumsy, in the space of as many sentences.

The results were, essentially, all the same: blasts of self-aggrandizing venom that seemed to have been gouted directly out of the veins of a very angry, very disturbed man, usually headed toward a punchline variation of Damon Knight’s ‘To Serve Man.’

His style — as he himself put it, he wrote assaults rather than still lifes — was hard-boiled noir mixed with lashings of Cordwainer Smith’s 1950 classic ‘Scanners Live In Vain,’ a heady roar of street gang angst, a wiry form of teenage rebellion that he nevertheless continued for much of his career and which passed over, or vice versa, into a bullish, combative real life. He wrote fast and with passion, and given the clattery wordiness of his staccato sentences, tumbling thought processes, and rudimentary plot advances, he typed as fast as he could think and he rarely revised the results much. I guess he wanted to be Neal Cassady as much as he wanted to be Cordwainer Smith.

Ellison landed stories and won awards, and he thought this justified his arrogance whereas in fact he hadn’t fully earned it. The result was the most insufferable of his personas, the bullish huckster who hated everybody else and thought himself king of the written word. The way the Ellison machine tells it, he’s the most significant science fiction author ever to live, and the only one to write fully from the heart, but from this remove — and the remove is widening — he’s just a mouse that roared, a pipsqueak sideshow of the red-faced child throwing a paddy in the corner because everybody isn’t looking his way. And since we who never knew him have little of his gentler side to commend him, this is the persona that will prevail.

Ellison inserted Ellison into everything he wrote. ‘Jeffty Is Five,’ for example, appears to be a story about a boy who lives eternally in a state of childhood grace, until he’s corrupted by the modern world, but it’s actually an old man’s diatribe about how things were so much better when Ellison was a kid. He means the late 1930s and early 1940s, when music was music not noise, when churned-out radio programs were the finest of art, when even the hicks and hillbillies loved one another, when war made heroes of us all, and when nobody even mentioned the blacks.

The disconnect here is yawning: so many of his stories were written purely for the pay, purely for a word-count and a cent-per-word remittance, that it’s hard to make for them the tempestuous outpouring of a wounded artist that he so often claims of himself. About them his anthologies wrap story-by-story introductions that can be unbearably self-important, great slabs of ego that seem intended to deny we (semi-literate, moronic, unworthy) readers the opportunity to evaluate the stories on their own merit.

This is certainly true of the handful of books of the 32-volume The Harlan Ellison Collection that I own. It’s even more true of the execrable The Essential Ellison: A 50-Year Retrospective in which you have to claw your way through fetid mounds of Ellison’s self-congratulation to find anything worth caring about.

And the upshot of all this is a man whose own contentious nature works against him, a man whose very name is copyright, meaning a legacy marked forever by an unfettered ego, a man sidelined from the more humble and deserving writers that crowd this genre by its own troublesome nature, a man so protective of his own genius that commentators like me could not have written articles like this while he was alive. Well, bully for you, Harlan. It’s not your vitriol that will be missed.

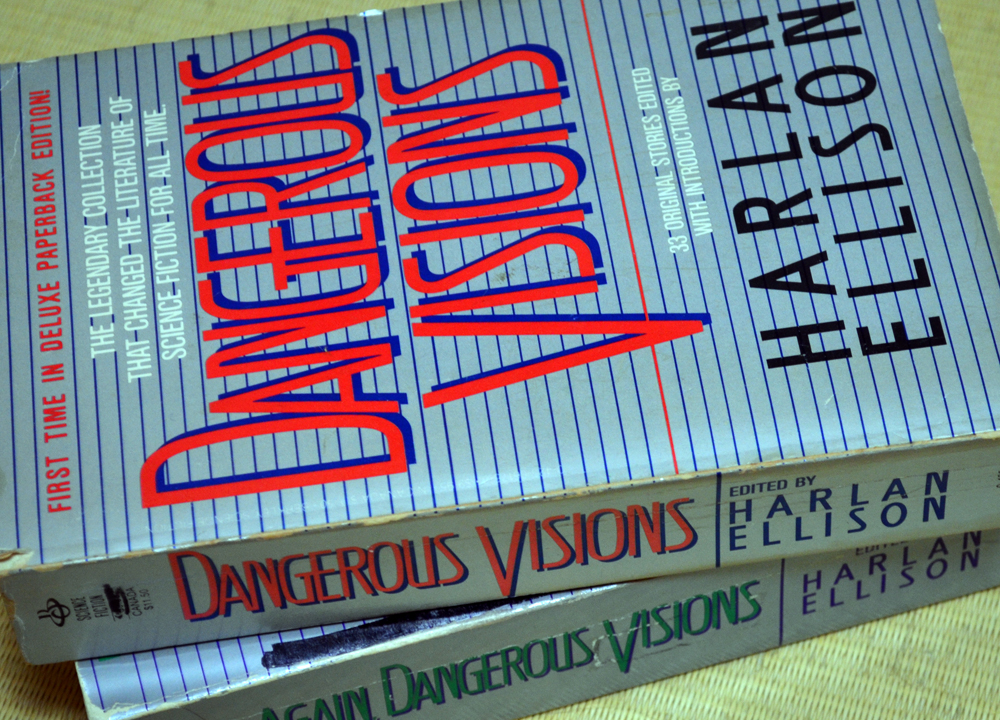

Instead of his own work, Ellison’s main claim to our collective memory will be the two anthologies of new stories he compiled in 1967 and 1972: Dangerous Visions (which did make it into SF Masterworks) and Again, Dangerous Visions. But just how dangerous do they seem now?

In the latter part of the 1960s, Ellison was riding a peak in the history of the genre. The pulp age was over. The golden age was over. A third distinct generation of science fiction authors had been moving into the scene ever since Philip José Farmer’s pioneeringly daring sexual work of the late 1950s. While American prurience largely delayed the cutting edge of the new themes there, a more liberal and experimental strand of science fiction blossomed in the UK on the back of a fixation with transgressive American writers such as William Burroughs. They coalesced under Michael Moorcock’s editorship of magazine New Worlds and introduced a revolution in the ways authors have thought about what science fiction means as a genre ever since.

Moorcock, nor indeed any of the authors he championed, never truly thought of themselves as a movement called the “new wave.” They were, of course, a new wave of young, hungry writers. But they were no more a movement than any other movement in the history of the genre, simply disparate authors finding common ground in their need to express their vision. The label, as Moorcock acknowledged later, was merely a means of gaining attention. “We need to talk of Movements in order to get moving,” he said. “We need to think, we’re eight blokes here, eight musketeers. […] Movements always break up very fast. The New Worlds group soon broke up (quite amicably) into individual writers, each getting on with his own work.” (Quoted in Colin Greenland’s The Entropy Exhibition: Michael Moorcock And The British New Wave In Science Fiction.)

The truth is that New Worlds had incubated talent and been publishing outrageous, transgressive, and forward-thinking new types of science fiction for years before Ellison decided to wedge himself into the narrative. With Dangerous Visions he undoubtedly helped to crystallize the new forms — as well as being instrumental in finally introducing them to the US — though that was all he managed.

Ellison himself skewered the term “new wave,” claiming the handle was falsely hung on Dangerous Visions when actually the book represented no wave at all. My suspicion is that what Ellison had wanted to achieve with Dangerous Visions was to increase the US market for the kind of shock, brutal work that he himself wanted to sell. He didn’t want to be part of anybody else’s movement. He wanted to carve space in which he, Ellison, was the figurehead. He, Ellison, got the premium word-rate. He, Ellison, was prophet and master.

Dangerous Visions certainly achieved this aim, at least for a short while. But the backlash against the new wave that the volume provoked put Ellison in an awkward position, so it’s unsurprising he distanced himself from what genre commentators considered the style.

It came down to economics, not art. American publishing houses saw their catalogs of old-style science fiction lose value. They pushed strongly back against European pretensions. The new wave was less well promoted, so it sold less — and there was always the deep, murky well of undiscriminating boys who could be attracted to robots and spaceships and who’d vote the difficult stuff out in the Hugos. Long before Star Wars consolidated this shift back downstream, editors like Judy-Lynn Del Rey at Ballantine were purposefully pumping the market full of new work in the old style, for example in the Stellar anthologies first published in 1974, in order to stab science fiction’s uplift in the belly. Ellison risked being wounded with all the other upstarts, many of whom (including Ballard and Moorcock) all but gave up on the genre in disgust.

I also suspect that in the early 1970s he became disillusioned with all forms of science fiction, which is why the intended third volume The Last Dangerous Visions didn’t happen even though, the way Again, Dangerous Visions tells it, the book was compiled and ready to roll on the publication of that second volley. He no longer cared about the very styles he had chosen to champion.

Certainly, in his later life he strove to be associated more with the mainstream of Great American Writers than with the genre ghetto, chasing longevity in the same way that Ray Bradbury had done. I’m not sure he achieved it. Contrarily, the aggressive image I’ve already mentioned marginalized him not only within the genre but outside it. Ellison chose to place himself on a separate pedestal to everybody else, and the result has been that nobody cares to look up at him regardless of what kind of writer he calls himself.

With this long remove, are Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions any good? Certainly they contain a sprinkling of some of the best writing of the period. They also contain acreages of dross.

Some of the stories that Ellison championed now seem like the worst of the era’s self-indulgence. It came with the territory. Genre writers-for-pay were told, by Ellison when he commissioned his all-new volumes, that they were now Artists to be considered Beyond Editorial Reproach. Their reaction — the best of them, anyway (it’s notable that Ellison struggled to fill his first volume with worthwhile work) — was what now seems like a pastiche of what made the British new wave so interesting. They all put on affected voices.

In particular, Farmer’s ‘Riders Of The Purple Wage’ is an excruciating sub-Joyceian word salad that actually begins that writer’s swift descent from one of the most genuinely fascinating voices in the “new wave” to one of science fiction’s most uninteresting and unimaginative voices once the wave had passed. Farmer clearly thought his European affectation a delightful jape. But Joyce had already been superseded in the European genre by Anthony Burgess — with Aldiss following close behind — and in the American genre by Burroughs — with Norman Spinrad on his way. Farmer’s work is both out of touch and pointlessly affected. Ellison seems to have bullied the Hugo into giving it a joint award it doesn’t deserve. It’s extraordinary to think that at the same time Ballard was busy formulating The Atrocity Exhibition, which itself stepped onwards from Burroughs.

To be fair, Farmer did still have excellent work in him. There was his story ‘Sketches Among The Ruins Of My Mind’ to come — but that was for Harry Harrison’s Nova series, not Ellison.

Others, in both volumes, are mediocre writing plumped up as if they were classics by Ellison’s fancy wrapping, and more awards followed largely because Ellison said they were award-worthy.

Indeed, the two volumes saw the British heart of the new creativity at an ebb. The stories Ellison commissioned from Aldiss and Ballard are not their best. Either of these authors at their peak would have chewed up everything else in Ellison’s volumes. They still might have, had there been a representative anthology of the New Worlds writers that could have had as much industry exposure and clout as Ellison’s. That would have scooped up every America-centric award in the genre.

It’s not a fair comparison, I know, but read a Langdon Jones or Michael Moorcock anthology of the same time. The difference is palpable. One of my all-time favorite anthologies, for example, The Traps Of Time (1968) is a head-bursting rush of excesses that makes Dangerous Visions seem pedestrian and dull. There’s work here such as Ballard’s ‘Mr F. Is Mr. F.’ that does what Ellison is trying to do only a hundred times better. There’s peak Aldiss in ‘Man In His Time,’ and superb head-hurting new horizons for the genre such as Jones’s ‘The Great Clock’ and David Masson’s ‘Traveller’s Rest.’ There’s Thomas M. Disch and Roger Zelazny. There’s a vision that actually does seem truly dangerous, and it’s not Ellison’s at all.

Naturally, this is not fair, like I said, because Moorcock’s anthologies were the cream of his crop, whereas Ellison’s stories are all new. Then again, Ellison’s writers rarely stepped up to the challenge laid down by their editor in the way that New Worlds writers stepped up to Moorcock’s. There’s nothing in either of Ellison’s volumes to match Pamela Zoline’s ‘The Heat Death Of The Universe,’ published by New Worlds in the same year as Dangerous Visions. She was American, this was her first story, and Ellison missed her. Instead, some of Ellison’s stories were old, rejects from writer’s “trunks,” purloined from workshops, or even submitted by literary agents and used to bulk up the page count.

I read Moorcock’s anthologies again and again. I rarely read Ellison’s, and then only the smattering of the best.

Actually, here’s an admission. I don’t treasure Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions much for the stories themselves. I treasure them because they give me a chance to spend time with Ellison.

I’d never bother with a book of autobiography or criticism or his other ramblings, even reviews from him, but in these volumes he enthuses about a thing he loves, and his shutters are down a little. His introductions see him at his sweetest and most naked. That’s priceless. Naturally, there are still all his unbearable affectations, but these are actually a pair of books about Ellison himself, with some short stories levered into the gaps to sucker in people who think they’re getting something else. They’re not. The wrap is the deal. Ellison is the deal. And he’s never once written better.

Flawed, for sure. Ellison had greater flaws than the Venus De Milo. There is, for example, his uncomfortable sexual politics, from calling all his contributors “men” in the first volume (even though a couple of them were women) to a rather simpering defense of feminist science fiction when introducing Joanna Russ in the second, making claims for the differentiation of women’s writing without having a clue that his bestest saved-till-last scoop was a story from a woman masquerading as a man, James Tiptree, Jr. But sweet nevertheless. I can truthfully say that I have not made it through every story in the two volumes. But I have read and savored every word that Ellison wrote.

And this gives me little hope for The Last Dangerous Visions. The feeling — and I may be wrong on this, since I have no actual knowledge of what’s planned for the 2024 release — is that the third volume never happened at the time because Ellison couldn’t write the long introductions for all the stories he’d gathered for it. He descended into a pit of block or ennui that wrecked the enthusiasm he needed to do it.

And what, then, is the point of the book if we don’t have Ellison’s voice to guide us through it?

What is certain is that Ellison’s intended contents will be altered, of necessity since the long debacle over the volume means many of the planned stories have been published elsewhere since, to match whatever the new editor or their publisher thinks are significant. In other words, it won’t be Ellison’s vision at all. Its main result will be to dilute Ellison’s memory rather than strengthen it, but paradoxically for those of us already on the man’s team, it will remind us just how much we miss him.

I’d love to spend more time with him, but if we can’t — well, then, I don’t want the third volume at all, thanks all the same.

Photo by Robert Maas of his well-thumbed secondhand editions of the two anthologies.